Securing Entry: RFID Is Making Us Safer

Introduction

In 2001, the database the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) used to check visa and passport applicants held about 7 million visa records and over 2 million passport records, according to the DHS.

Further, they said that, “If a visa applicant turned out to be a possible match for a terrorism-related CLASS record, the consular officer requested a Security Advisory Opinion (SAO) from the Visa Office in Washington. Such requests were sent via cables, as were the Department’s responses. This multi-step cable process to communicate with posts and to coordinate with other government agencies resulted in long wait times for both the consular officers and the applicants.”

A simpler, more efficient way

By 2005, though, those long wait times were going to change – at least in theory – as RFID was introduced to the average American passenger traveling internationally. Today, the State Department issues both passport cards and passport books that are “smart” enough to read our information, the former at a distance and the latter at close range.

The U.S. employs biometrics, which can be obtained through facial recognition, fingerprints, or the scanning of irises, but apparently requirements can vary.

Cover of a US biometric passport.

Michael Holly, Senior Advisor for International Affairs, Passport Services in the U.S. Department of State Bureau of Consular Affairs told RFIDinsider that “We use both fingerprints and facial recognition [for visas]. We’ve also studied the use of iris images.”

He did not elaborate further, but it’s widely speculated that scanning iris images is not as reliable, and thus less popular, than scanning fingerprints and recognizing faces. For passports, moreover, a digitized and readable photo is used, forgoing fingerprints on its contactless chip.

Insofar as the Government’s rationale behind RFID’s use, Holly claims the history far precedes 9-11, a common barometer for measuring the nation’s security practices. Indeed, according to the U.S. Government, RFID has been used along the nation’s land borders with Canada and Mexico since 1995.

While Holly didn’t spell this out, the new passports have been designed to better protect the public from terrorism, even though it’s arguable whether or not they are also easing hassles at airports. Toward that end, there are bells and whistles attached to modern-day passports, and depending on whether one has the “card” or the “book”, the technology differs.

“What we provide to a U.S. traveling citizen bearing a passport card is a protective sleeve with that document,” Holly says. “But with a passport we do a number of things – these are two different technologies: proximity and vicinity.”

He says with a passport card “vicinity technology” is employed; and a number of things are done to protect it “from the possibility of skimming data from the chip, and eavesdropping. We use anti-attenuation tape, a skimming sleeve that blocks the possibility of someone trying to skim data from the chip if the book is closed,” he says.

The borders agent can thus obtain information discreetly, and in real time, according to Holly.

“They’re [the passport issuers] using PKI (public key infrastructure) and in association with the RFID chip we can …confirm data that appears on the passport’s data page and [which one] can authenticate using the digital signatures,” he says.

Silencing the critics

Obviously, in an era when a plane can go missing for weeks or months, and two passengers can board with stolen passports, security at least worldwide is hardly foolproof. Nevertheless, Holly believes that over about the past decade, the American traveler’s experience is far more secure than it was in the halcyon days of early air travel.

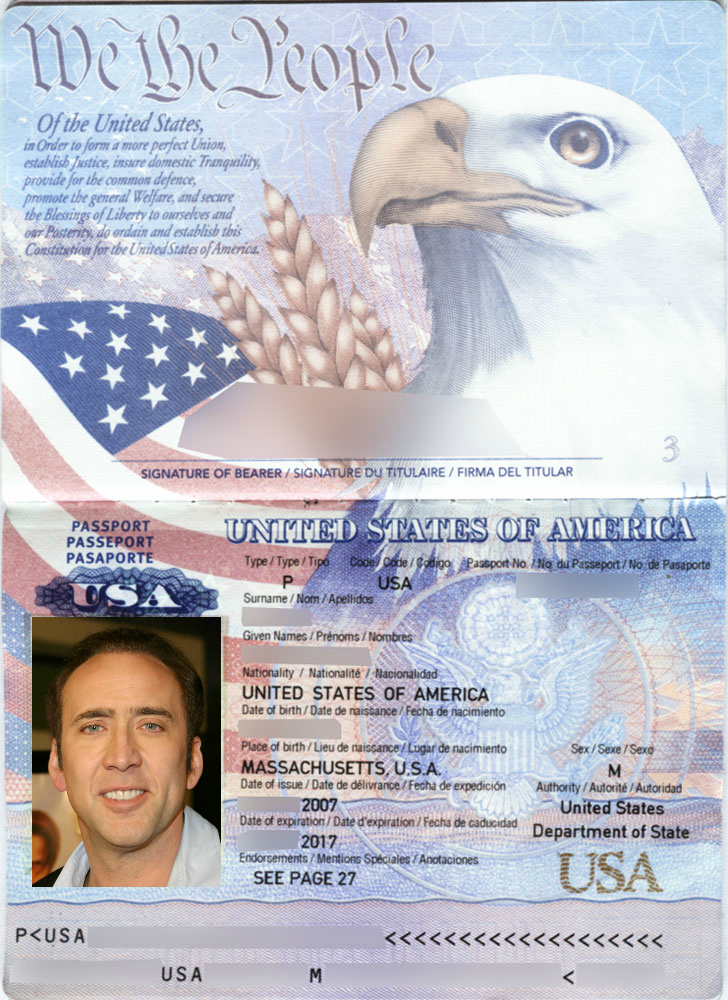

“We use a security protocol known as the “basic access control” that requires, in order for the chip to communicate with a reader, that [the passport owner’s] book must be open, that the machine- readable zone be read.”

He says this “zone” is two lines of OCR code at bottom of the passport page, and from which “a number of pins are derived, and then once that happens, the chip will communicate with the reader, releasing the data on the chip.”

The OCR code is visible at the bottom of this hypothetical Nic Cage biometric passport.

In the case of passport books, the readers are at the customs booths for use upon entry to the foreign country. But in the case of cards, which he explains are commonly used when U.S. citizens travel by car from the northernmost and southernpost parts of the country, the data is read from a greater distance. (See article on toll booth RFID use.)

Both [the card type and book type] are passports but the book uses RFID proximity technology, he explains. “The chip in the passport book is a microprocessor. It stores data on it. …The passport card does not store any data. It simply points [via a recognized serial number] to a record stored in a secure database.”

Partners in protection

The Netherlands-based Gemalto, a global digital security firm, has been working with the U.S. Government for several years on rolling out RFID for use on or with passports. Gemalto says on its website that in August of 2012, the Government Printing Office (GPO) awarded the company with a second consecutive five-year contract.

“Gemalto first partnered with [the] GPO in 2006 following stringent evaluations to meet agency requirements,” the company says on its site. “Gemalto is to supply its latest ICAO-compliant Sealys eCovers as well as support for the lifetime of the agreement. In 2011, the State Department issued 11.4 million ePassports to American citizens.”

Any other vendor information would be attainable from the GPO, but one can assume that the Office employs not only the latest technology but the most tightly secured.

That being said, Holly claims that the State has nothing to hide insofar as the type of technology used or how it’s used, and says they are completely transparent about the process.

Critics of RFID use in passports include the traveling public, responsible newspaper journalists and editors and other concerned citizens. Some websites have even set up lessons on how to disable the RFID chip, which is completely illegal; the most popular method apparently being with a hammer.

That being said, Holly insists RFID and passports are a marriage that will last, and meanwhile, are making both the U.S. Government’s as well as the traveling public’s lives much easier – and more protected.

He stresses too that both the usability and reliability of passports is now heightened, whether for the consumer or for those who must read the data.

“The passport and the token must be within close proximity. [But] in vicinity, with the card, it can be pinged at a distance of 20 to 25 feet,” he says.

Conclusion

If you would like to learn more about all things RFID, check out our website, our YouTube channel, comment below, or contact us.

To read about more real world RFID applications, check out the links below!